Writers, artists, thinkers.

My own intellectual development was lengthy. It took me a long time to locate myself intellectually and to define the subject positions which were important to me as a writer. Anyway, I thought I would put up a page with some of my own reflections on a few writers, artists and thinkers who have been important to me...

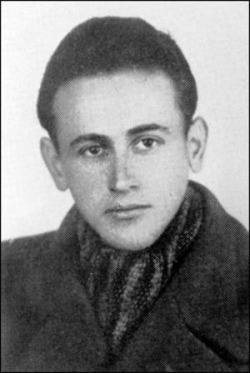

Paul Celan

As for Celan's poetry itself I have always conceptualised it in terms of an image. The image is of a man walking through some vast wilderness of desolation, like those ruined cities of Germany after they had been flattened by Allied bombing raids. I imagine that whilst wandering through this waste land the man comes across scraps of paper, on which are printed fragments of text which have survived the inferno. On this scrap of paper no more than a word or a few letters are still legible; on another, perhaps, a phrase, or the beginning or end of a sentence. To my mind Celan's poetry comprises a mosaic of these textual fragments. Thus there are two valid interpretative approaches towards it. In the first place the critic can attempt to reassemble the linguistic context from which these textual scraps have been wrenched by destruction. This would constitute an infinite task. On the other hand the reader can ponder how it is Celan has come to reassemble these fragments in their specific combinations in the poetry. What is deeply unsettling, indeed terrifying, about Celan's writing is the sense it generates that in order to finally understand this you would have to understand how, for instance, the Jews of Budapest perished in Auschwitz. Not, of course, by simply grasping the details of their historical narrative from the outside. But rather by comprehending what is innate in us: our "human, all too human" potential to perpetuate such acts. Each sentence in Celan registers the immeasurable, incalculable desolation of this problematic. Each sentence is a limit and a going beyond a limit somewhere else. There can scarcely be any other poetry extant which better exemplifies Rilke's dictum that "beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror".

I ought to add that this way of thinking of Celan's work is certainly biased towards his early writing, the best translations of which, by far, are by Michael Hamburger. His later work seems to me to be something else again, and I am not au fait with some of the more recent translations of it.

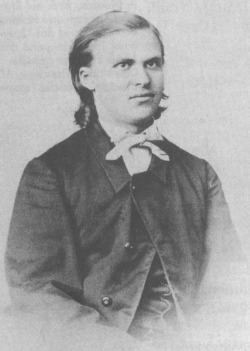

Friedrich Nietzsche

Nietzsche’s philosophy is so fundamental to me that I almost trace my discovery of his writing to the birth of my own capacity to think. There are so many dimensions of his work which are inspirational that it would be impossible to do justice to them in a couple of paragraphs. Let me examine, then, just one, his much misunderstood theory of tragedy. In his discussion of tragedy it is essential to grasp that, in contrast to Aristotle, he seeks to understand the problem from the perspective of the artist, a perspective which he claims has been missing in the history of thought. Nietzsche, of course, associates tragedy with Dionysian joy. However it would be absurd to extrapolate from this the idea that he thereby means that an appropriate response to a performance of, say, King Lear, would be to leave the theatre feeling joyous. On the contrary his theory properly addresses the question of what Shakespeare was feeling when he was writing King Lear. This, precisely, is the lost perspective of the artist which Nietzsche is concerned to restore. He affirms, simply, that Shakespeare would have been feeling joyous whilst writing the text, although he might very well have felt something entirely different watching a performance of the play in the theatre, assuming he could have heard anything above the infernal cracking of nuts. Everything we know about Shakespeare, incidentally, points to precisely this conclusion. You cannot possibly write the number of tragedies Shakespeare did in a relatively brief period without enjoying doing so.

Nietzsche’s philosophical methodology invariably proceeds by returning to the origin of a concept and immediately advancing a bold hypothesis in respect of it, thereby turning received opinion on its head. In the case of the origins of Greek tragedy, for instance, he makes a startling and challenging claim, namely, that the original audience were themselves the artists of the drama. This should be understood as a riposte to Aristotle whose theory of tragedy, according to Nietzsche, is concerned with the perspective of the audience (his audience, Aristotle's audience). By contrast Nietzsche insists that, at the origin of tragedy, there was no gap between audience and artist in a modern sense at all. It is precisely this "passionate unity" which, Nietzsche claims, “we moderns” have lost. This is because, for Nietzsche, tragedy originates in a religious festival, in a Dionysian orgy of the worship and celebration of existence. On this view the individual characters in early Greek tragedy are the hallucinatory projections of the original audience, the principle of individuation made flesh. This original audience is, according to Nietzsche, still extant in the form of Greek drama; it can be glimpsed in the perspective of the chorus itself. Note that, and crucially, this means, for Nietzsche, the audience is on the stage of the artwork in Greek theatre.

Nietzsche’s discussion of tragedy is highly significant for all kinds of reasons. But let me focus on just two. In the first place tragedy functions for Nietzsche as an epochal site in Western culture since it was in the context of tragedy that Socratic thinking was born. The most salient fact about Socrates, in other words, as Nietzsche continually emphasises, is that he went to the theatre. The birth of "Western reason", in short, did not occur in a cultural vacuum. In fact it originates in a full blown attack on the values implicit in the early dramas of the agon. Thus Nietzsche’s lost “perspective of the artist” functions as a kind of “vanishing mediator”, to adopt Fredric Jameson’s term, at the birth of Socratic dialectics. Nietzsche’s entire philosophical project is really an attempt to renew this lost process of mediation. The index of this attempt, in Nietzsche’s writings, is style. Every sentence Nietzsche writes is a living rebuke to philosophy to at all points remember its cultural and sociological origins in drama.

Secondly, Nietzsche’s theory of tragedy remains important today in what it has to say to us about the nature of a radical aesthetic practice. What Nietzsche continually demands of modern artists, famously, is that they participate in the “rebirth of tragedy”. Of course, he originally thought of Richard Wagner’s works as being exemplary in this respect, but later changed his mind about this. I want to argue that this demand for a “rebirth of tragedy”, so far from being a reactionary attack on avant-garde practice, as it is so commonly misunderstood, actually contains the seeds of its renewal. For it is now possible to see that such an attempt would formally constitute no more or less than the construction of the audience itself as the creator of the aesthetic work. His writing, in other words, puts the audience once again, as in Greek drama, back on the stage of the artwork. I would like to suggest to you that it is precisely this methodology which is operative in a text such as Ulysses, where the receiver has to actively construct textual meaning, rather than remaining a passive participant in its movement. The great works of aesthetic modernity, in other words, formally renew Nietzsche's conception of tragedy's rebirth, even though you could scarcely argue that they restore its lost, joyous content. To recover a sense of this, in turn, you need to think about what is going on in popular music. It is highly significant in this respect that, having come to reject Wagner in his later years, Nietzsche avowed that his preferred form of music were those melodic songs to be found in light Italian operas. These songs are, unquestionably, among the original sources of popular music, since, precisely, anyone can sing along to them. Is this not also an instance of how modern art places the receiver back on the stage of the artwork? Who knows, perhaps when we hum along to a tune by the Beatles we are revisiting in some way that original Dionysian celebration of existence which philosophy has done so much to obscure.

If you are interested in Nietzsche's philosophy then a good way into it today is via Alenka Zupancic. Her book The Shortest Shadow is one of the most important ever written about Nietzsche, although it does presuppose a familiarity with some Lacanian conceptions. Friedrich Nietzsche himself died in 1900, after a long and debilitating mental illness. His work remained unread outwith the coterie of a handful of intellectuals for much of his life. Now the books which he wrote are considered to be one of the philosophical foundations of modernity, of the world in which we live. This extraordinarily sensitive and intelligent man – who, to my knowledge, was incapable of harming a fly - fulfilled his own criteria of genius, namely, as an individual who is born in the wrong historical era and who, for that reason, has something interesting to say about the intellectual outlook of his contemporaries. His life, so far from being that of a “romantic hero” or a trendy intellectual, is actually the testament to an outstanding ethical and intellectual heroism which, aside, perhaps, from the life of Marx, is unequalled in the history of modernity. In the cynical and embittered world in which we live it is a life which is no doubt barely comprehensible. And yet, even in his many private failings and in the frequent inadequacies of his philosophy, his commitment to thinking endures. As he said himself: “All my errors stay behind to lead”.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo left a proof

On the Sistine Chapel roof...

Proof that there's a purpose set

Before the secret working mind:

Profane perfection of mankind.

"Under Ben Bulben" W.B Yeats

Michelangelo's monumental images form a permanent point of reference in western culture. His work and life are seminal, of course, to the entire conception of the modern artist, not least because of the way in which they were mythologised by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists. My own theory of aesthetic composition, which revolves around the notion of clearing away extraneous language, has clear points of contact with Michelangelo's theory of sculpture. This latter holds that the completed figure is already pre-existent in the unhewn block of marble; hence sculpture becomes the art of clearing away extraneous matter. Analogously for me, writing is, on one level, the revelation of annihilation; that is, technique delivers the negation of the infinite linguistic possibilities with which any writer is confronted in the act of composition; the linguistic essence, in other words, which technique discovers in the form of the finished poem, has been virtual in the language all along.

Fortunately, thanks to the internet, you can now at least view all of Michelangelo's work online. By contrast I never really had any awareness of Michelangelo's works until I was in my early 20's. I still remember opening a book of his images for the first time and coming across pictures of his Pieta of 1499. The experience was like the visual disclosure of that famous last sentence in Rilke's "Archaic Torso of Apollo": "You must change your life". That occurred twenty or so years ago. And I still think of Michelangelo today as the epitome of the western artist.

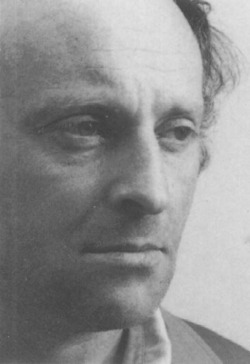

Joseph Brodsky

One of the reasons Brodsky is so important to me is because I discovered that I could write poetry through reading his collection To Urania. For some reason his poetry triggered something in me which enabled me to write. Through reading his work I suddenly grasped how I could and should write.

Brodsky was once jailed in the old Soviet Union for refusing to do any "socially useful" work. He was working, he argued, as he was a poet. His commitment to poetry was absolute as was his understanding of the historical significance of poetry, which he once described as "the essence of world culture". I have always thought of my experience in respect of his work as constituting the paradigm of how poetry can, in contrast to the assertion made by Brodsky's favourite poet, W.H Auden, make something happen. Poetry represents, for me, the chance of an Event. Poetry is revelatory and no one can predict who has the revelation. This is how poetry participates in the immortal. It is language striving to arrive at the eternal, not in itself, but in its transforming power, in its ceaseless relation to alterity. In my case Brodsky's writing completely transformed the conception I had of myself and my notion of what writing should be.

Brodsky's best poetry is probably to be found in To Urania, which he translated into English with Alan Myers, although some of the poems in that book were, in fact, originally written in English. However he also came up with some truly superb crtitcism, which you can find in his book Less Than One. In particular, his essay on WH Auden's "3rd of September,1939", remains the epitome, for me, of a poet bringing all his ethical and aesthetic intelligence to bear on a modern text. I highly recommend it.

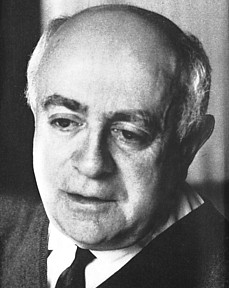

Theodor Adorno

I became interested in Adorno through my early engagement with Walter Benjamin's work. In those days I was initially somewhat dubious in respect of his writing. Now I increasingly think of Adorno as probably the most important writer on aesthetics in the history of the twentieth century. In particular his book Aesthetic Theory is, for me, absolutely seminal to the way in which I think about writing. Much of what I now try and do as a writer can be conceived as an attempt to mediate Adorno's ideas in some way.

Adorno's strength as a writer lies in his ability to transform the power of negativity into a principle for thought. Of course the capacity for dialectical negation has always been an integral part of the Hegelian intellectual tradition of which Adorno's work is an extension. Its power lies in its capacity to realise this negativity formally, as no more or less than a constituent of style. In Adorno's works the content of sentences formally conveys the power of this negativity, even while their form departs to its own place. This place, of course, is utopia. Adorno, like Benjamin, is a thoroughly messianic thinker. His language ought to be grasped from the perspective of the eye of the needle through which it is possible to glimpse the absolute salvation and redemption of humankind. Needless to say, in Adorno's works, this perspective is perenially disappointed. Humankind, in other words, remains unredeemed. Adorno's sentences are stylistically loaded with the desperate realisation of this insight. He is like the child who entered the world with the highest expectations, only to discover that it was banal and evil after all.

Slavoj Zizek once accused Adorno of failing to conceptualise what Lacan calls the Real. For Zizek, in other words, Lacan conceptualises what is for Adorno merely implicit. To this critique, on Adorno's behalf, you could only answer, "Guilty as charged!" This is because, for Adorno, the formal expression of the concept is his bridge towards a vision of paradise. It is precisely through the notion that the concept continually fails to coincide with our experiences which constitutes us as humans in the first place. Note, that, for Adorno, things are not the other way around. This is why writing exists for him, as for Benjamin, in a tangential relation to the incommunicable. If you were looking for the basis of a critique of Lacan's notion of the Real, incidentally, this might be a useful starting point. Doesn't Lacan's notion fall down, in other words, precisely because, at least in Zizek's interpretation, it is linguistically naive, in the sense that the Real exists as the name of a concept which has already been predefined? Doesn't this way of philosophising, aptly enough, in fact, given its psychoanalytical origins, merely define or diagnose the phenomena linguistically, from the outside, rather than attempt to mediate it? Adorno could no more have accepted the idea of the Real than he could have accepted the notion that truth could be filled in philosophically, with some kind of positive content. Truth, in fact, is, for Adorno, precisely, a name which has no positive content. Hence the significance of art. Truth, in short, could never tell us what to do. To believe otherwise, would, precisely, constitute the betrayal of truth. Truth can emerge only negatively, through style, through the way in which Adorno forms sentences.

Sylvia Plath

I first came across Sylvia Plath's work when I was an undergraduate. In those days, having just properly discovered poetry, I was reading as much of it as I could get my hands on. Of course Plath was a famous name but, precisely for that reason, I was initially suspicious of her reputation. This is because, in my experience, the amount of publicity which a modern writer's work attracts in the English speaking world invariably stands in an inverse relation to its value. But this was not at all the case, as I soon discovered, with Sylvia Plath. On the contrary her work immediately struck a chord with me. In particular her later poetry is tremendously instructive for the way in which it suggests how a poem can move, of how the discovery of acoustic relationships in the language can propel the poem onwards, to the discovery of a new place. The difference between Plath's early and later writing, for instance, which has often been remarked upon, is the difference between a writing which has been conditioned by the eye and a writing in which the acoustic dynamics of language have taken over, although, having said this, Plath's later work still delivers the most extraordinary visual metaphors now and again. The late poems convey a sense of a writer who has grown confident enough to abandon her individuality; instead the raw power of technique has taken over. They demonstrate how technique generates its own momentum and propels language into the future irrespective of its producer. I know of no poetry which more powerfully conveys the sense of Brodsky's great statement, that "a poet is a combination of an instrument and a human being, with the former taking over from the latter. The sensation of the takeover", Brodsky adds, "is responsible for timbre. Its realisation, for destiny." This is exactly the kind of insight that Plath herself would have relished.

The more I think of Sylvia Plath the more I wonder what might have become of her had she been exposed to a different set of intellectual influences. One of the great problems with her work is that it is full of all kinds of entirely spurious conceptual mumbo jumbo, such as ouija boards, the notion of "fate" etc. Most of this is, of course, from an intellectual point of view, complete dross. And yet, like WB Yeats himself, who also went in for this kind of mystical twaddle, she nevertheless managed to produce some remarkable poems from these materials. This only goes to show the extent to which the technique of great poets is capable of transforming anything it comes into contact with. Like the mystical king it can turn any old dross into gold, merely by laying a finger on it. This is one of the reasons, incidentally, why it is entirely futile to approach any art from a prescriptive point of view, by banning the use of certain materials in advance. This is invariably the approach adopted by critics who imagine you can decide what is a suitable material for art on grounds of taste or morality or whatever. The lesson to draw from Plath's work, like that of Yeats, is that great technique has the power to redeem its materials by transcending them in the direction of truth. Coming up with an answer as to why or how this occurs is one of the most difficult problems art raises. So long as technique is perfected enough great works can just as easily be conjured from elephant dung than from the chronicles of Holinshed.

Of course, having said all this, it is important to emphasise that Plath was herself highly intelligent and yet, if you think about the radical intellectual discoveries which were being made in France at the time she was writing - many of which, of course, she was keenly aware of - then you can't end up with anything other than a sense of solidarity for her as well as a lingering sense of how things might have worked out differently for her had she lived just ten years later and been exposed to the intellectual movements which swept Europe during the sixties. Instead her poetry is a curious amalgam of some quite progressive ideas about women on the one hand and a rag bag of intellectual awareness's on the other. For any poet, actually, it can often be fiendishly difficult to properly integrate their materials intellectually. There are all kinds of different reasons for this, of course, partly because the experience of writing poetry is so intense, and partly because poetry stands in a relation of tension with the concept, to say the least. This isn't to imply, of course, that poetry can't be conceptualised. Rather, what it suggests is that poetry can't be conceptualised before it is produced. It may well take a poet a considerable period of time to begin to intellectualise their writing in a way which is adequate to it, assuming they are ever able to do so. In fact the vast majority of poets probably fundamentally misrecognise the philosophical content of their own writings - T.S. Elliott would be an example of this. Whatever you think of his critical writings, after all, they bear only a tenuous relation to the aesthetic practices in which he was engaged.

The most salient fact about Sylvia Plath now, looking back at her work in the years since it was produced, is that, for whatever reason, she never managed to attain the space and time which she needed to frame her writing in an adequate discursive context. For a poet of her ability this was a catastrophe. Instead, during those breakneck last couple of years of her development, it must have seemed to her that she had worked herself into a technical place which was both entirely remarkable and completely disconcerting; as we now know this produced a situation in which suicide became an option which she explored. For make no mistake, Sylvia Plath was fully aware of the greatness of the poems she was writing towards the end of her life. And what response did this poetry elicit? A life of solitude, screaming kids, and that ghastly, public school world of the London literati in the late 50's and early 60's for whom her late poetry must have been both baffling and disconcerting. This was the world she herself, as a young woman, had bought into. In encountering it, from the perspective of her later verse, she must have felt as if her life had been no more or less than a betrayal of her very being, of everything most important about herself.

How good was Sylvia Plath? I can only say that, to my mind, she was one of the four or five most naturally gifted poets in the English language since Wordsworth. Yes, she really was that good. And if you are looking for a day on which to celebrate the anniversary of feminist writing, or, indeed, modern poetry itself, then how about the 1st of February 1963, that miraculous day when Sylvia Plath wrote not one, not two, but three of her finest poems: "Kindness", "Words", and my own personal favourite of all her works, "Mystic". The word miracle scarcely does justice to it. "Does the sea/ Remember the walker upon it?" as Sylvia Plath asks in "Mystic". Yes, Sylvia, in the constituency of poetry it does. This is how art returns us to the existent again, only to intimate a life beyond it. The last line of "Mystic" reads: "The heart has not stopped."

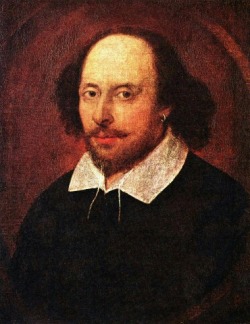

William Shakespeare

Bridges to the Body takes up Benjamin’s conception of allegorical writing in order to evoke a new image of the production of what I have called elsewhere on this site the aesthetic subject. In so doing it seeks to perpetuate a non-romantic version of the construction of subjectivity whilst remaining squarely within a recognisable lyrical paradigm, a formidable enough task given the ubiquity, even today, of the correlation between romantic ideology and the ontology of the lyric. To be sure there is little immediate sign of this in the opening poems of the text, which inhabit a more or less conventional romantic medium. The significance of these poems is transformed, however, when viewed from the perspective of subsequent textual developments, a salient instance, incidentally, of how what Adorno used to call articulation manifests itself retrospectively, as materials come to be mediated in the temporal dimension of reading, as form acquires the momentum of aesthetic progression. The best way into thinking about how this allegorical dimension of meaning operates in Bridges is to return, once again, to the aesthetic subject who goes by the name of William Shakespeare, since his writing presents an exemplary instance of the construction of such a subject prior to romanticism. After all, the astonishing variety of Shakespeare's texts, the sense they generate of a constant sensual and intellectual experimentation, a testing and dramatisation of multifarious existential possibilities, enables these works to be interpreted as an allegory for the production of his own subjectivity, as if subjectivity itself involved no more than the aesthetic formation and dissolution of a series of disparate subject positions. Shakespeare’s aesthetic subjectivity, so far from being posited in the first person as in romantic literature, emerges through the autonomy of stylistic and thematic progression, through the parade of a sequence of dramatic masks, beneath which there is no stable identity to be found.

It is precisely this technique which is utilised in Bridges to communicate the construction of the aesthetic subject Paul Harrington and it is for this reason – and this reason alone, incidentally - that it is possible to argue that poetic practice is here directly comparable to Shakespeare’s own. Bridges describes a movement from a recognisably autobiographical first person enunciation towards the annihilation of the romantic subject or self and it arrives at the new perspective of "writing the impossible" precisely in order to construe a revolutionary image of the production of the aesthetic subject in the allegory. But what is at stake, precisely, in this kind of allegorical construction? Why, for instance, is it possible to hold that this form of literary representation is more politically progressive than some mere romantic articulation? To answer this question it is well to return to Benjamin who argues that it is precisely because there is no necessary relation between the allegorical signifier and its signified which reveals allegory as a politically responsible form since what this form demonstrates is the contingency of how meaning is produced as such. What allegory demonstrates, in other words, is the extent to which meaning is historically and politically constructed and is, as a consequence, open to change. In respect of Shakespeare, for instance, it is perfectly possible to read his texts without any reference to this allegorical dimension of meaning; as is well known all of his plays are autonomous entities in their own right and it is unlikely that Shakespeare himself would have understood his work in this allegorical manner. In the same way all the poems in Bridges can be read independently, without any awareness of the allegorical movement to which they contribute when encountered in the context of the book. Indeed, in both instances, the allegorical meaning emerges only when the texts are viewed from a specific temporal vantage point, what might be termed an anamorphic perspective which opens at the end of the process of reading. In the case of Shakespeare's texts this perspective is available only many years after their production, in the romantic era, when the problem of subjectivity had emerged in its modern form. It is only at that precise historical moment that the allegorical dimension of his writing can be properly grasped or seen; it is only at that moment that Shakespeare can become a Subject in the modern sense. (Indeed, as is well known, the romantics largely invented their conception of genuis to account for the problem Shakespeare posed for their theory of subjectivity, which is to say, to explain what was inexplicable to them). And similarly the problem which Bridges to the Body raises is the question of how we ourselves confer the status of the Subject on the Other in our own present, the question of who (or what) becomes a Subject for us.

Shakespeare’s most important poetry is undoubtedly to be found in the dramas he wrote from around the mid 1590’s onwards. These are amongst the most significant texts to be written in the English or indeed any other language. What is so striking about many of these texts today is the vivid contrast they present with the pathetic timidity and circumspection of so much contemporary literature. If you think of characters such as King Lear or Othello, for instance, then you are immediately in the world of people who are at their wits end, at the utmost extremity of their being, and who express this in a poetry of great emotional range and power. What does the 20th century give us by contrast? J Alfred Prufrock and Leopold Bloom. The discrepancy is so great as to be completely ludicrous. Indeed I have often thought that the absurd lionisation of Shakespeare nowadays is actually a reflection of the unease of the literati at taking on these themes. In this sense the history of English literature has actually marked a departure from (or betrayal of) the Shakespearean aesthetic. As for Shakespeare’s tragic dramas themselves they invariably portray individuals of extraordinary linguistic complexity in situations of catastrophic isolation and there can be little doubt that these are essentially allegorical explorations of Shakespeare’s own existential situation. Characteristically, however, this truth content emerges only on the level of the allegory – precisely because, presumably, it would otherwise have been completely incommunicable to his contemporaries and, no doubt, to Shakespeare himself.